- Home

- Paula Manalo

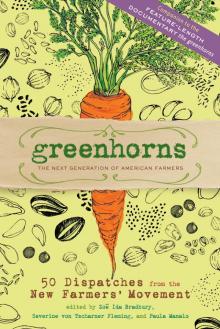

Greenhorns

Greenhorns Read online

PRAISE FOR

greenhorns

“If we are very lucky, the Greenhorns will have their way and give America back its family farms.”

— Molly O’Neill, author of One Big Table: A Portrait of American Cooking

“Amid the many sad trends of our day, nothing makes me happier than the recent USDA proclamation that for the first time in 150 years the number of farms in America is on the rise. If you want to understand why, and if you want to feel the vigor and love now returning to the land, this book is the place to start!”

— Bill McKibben, author of Deep Economy

“Right now, there is a whole generation of young, energetic, focused new farmers learning the craft, finding land, starting businesses. These are hard-working, dedicated, entrepreneurial folk, and all across the country they are producing exceptional food for their local communities. If you want to know what the voice of this powerful movement sounds like, this is the book for you. It is one of the most optimistic stories in America. The Greenhorns have put together a collection as satisfying as the food these farmers are producing.”

— Kristin Kimball, author of The Dirty Life

“The Greenhorns are my heroes. They are the face of America’s new agrarians — mostly young, educated, ready for hard work, passionate, and rooted in community. I really believe they are our future, and we’re damned lucky that they are. Their essays are insightful, thoughtful, and hard to put down. What a wonderful collection! I will recommend this book to everyone.”

— Deborah Madison, author of Local Flavors and

Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone

“Hooray for the Greenhorns! Networking young farmers from coast to coast, they have become a formidable force in our new agricultural revival, spreading resources, sharing skills, documenting their experiences, and advocating for change in our agriculture system. These essays offer serious food for thought, especially for anyone considering taking up the hoe — no matter whether young or old.”

— Sandor Ellix Katz, author of Wild Fermentation, The Revolution Will Not Be

Microwaved, and The Art of Fermentation

“This collection of young farmers’ stories is a cornucopia of gifts from the earth. I learned with pleasure about a group of people who are turning the world into a much better place.”

— Les Blank, filmmaker

greenhorns

50 Dispatches from the New Farmers’ Movement

edited by

Zoë Ida Bradbury, Severine von Tscharner Fleming,

and Paula Manalo

illustrations by

Lucy Engelman

The mission of Storey Publishing is to serve our customers by publishing practical information that encourages personal independence in harmony with the environment.

Edited by Carleen Madigan

Art direction and book design by

Carolyn Eckert

Illustrations by © Lucy Engelman

© 2012 by Zoë Ida Bradbury,

Severine von Tscharner Fleming,

and Paula Manalo

At Storey Publishing, we’re committed to producing books in an earth-friendly manner and to helping our customers make greener choices. This book is printed with recycled papers and vegetable-based inks.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages or reproduce illustrations in a review with appropriate credits; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means — electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other — without written permission from the publisher.

The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without guarantee on the part of the author or Storey Publishing. The author and publisher disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information.

Storey books are available for special premium and promotional uses and for customized editions. For further information, please call 1-800-793-9396.

Storey Publishing

210 MASS MoCA Way

North Adams, MA 01247

www.storey.com

Printed in the United States by Versa Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Greenhorns / edited by Zoë Ida

Bradbury, Severine von Tscharner

Fleming, and Paula Manalo.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60342-772-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Farm life–United States–

Anecdotes. 2. Agriculture–United

States–Anecdotes.

I. Bradbury, Zoë Ida. II. Von Tscharner

Fleming, Severine. III. Manalo, Paula.

S521.5.A2G75 2012

635.0973–dc23

2011051495

contents

INTRODUCTION

SHOVEL SHARPENED, SHOVEL READY

CHAPTER ONE

BODY-HEART-SOUL

The Physicality of Farming

BY JEFF FISHER

Farmer-Mama

BY SARAH SMITH

Doing. Instead of Not Doing.

BY EVAN DRISCOLL

You Are Not Alone

BY MEG RUNYAN

Two Pigs and True Love

BY ANDREW FRENCH

The Fruits of My Labor

BY MAUD POWELL

Surrender

BY COURTNEY LOWERY COWGILL

CHAPTER TWO

MONEY

How Not to Buy a Farm

BY TERESA RETZLAFF

Worth

BY BEN JAMES

Learning to Measure Success under the Big Sky

BY ANNA JONES-CRABTREE

In Praise of Off-Farm Employment

BY CASEY O’ LEARY

Fear of Debt: Should I Finance My Dream?

BY COURTNEY LOWERY COWGILL

CHAPTER THREE

LAND

Landing Permanency/A Permanent Landing

BY JACOB COWGILL

I Figured We’d Buy a Small Piece of Land

BY LUKE DEIKIS

Time on the Farm

BY BEN JAMES

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bugs

BY MK WYLE

The Secret Life of Fruit

BY JOSH MORGENTHAU

CHAPTER FOUR

PURPOSE

Purple Flats BY NEYSA KING

Write It Down BY JENNA WOGINRICH

Growing Not for Market

BY DOUGLASS DECANDIA

What to Do If You Think You’re Not Good at Anything

BY A. M. THOMAS

Farming in the Web of Interconnectedness

BY SARAJANE SNYDER

Farming with Two: Pleasure and Independence

BY EMILY OAKLEY AND MIKE APPEL

CHAPTER FIVE

BEASTS

Reflections of a Rookie Farmer BY JUSTIN HEILENBACH

What I Learned from Gwen BY CORY CARMEN

The Ambush BY CARDEN WILLIS

Notes from a Novice Horse Farmer BY ALYSSA JUMARS

Moral Clarity through Chicken-Killing BY SAMUEL ANDERSON

The Gift BY KATIE GODFREY

How Animals Sell Vegetables (and Make You Tired) BY LYNDA HOPKINS

Two Farmers, 350 Chickens, and a Hurricane BY KRISTEN JOHANSON

CHAPTER SIX

NUTS & BOLTS (& DUCT TAPE & BALING TWINE)

On the Rise

BY SARAH HUCKA

Potato Digger

BY ERIN BULLOCK

The Dibbler

BY JOSH VOLK

Tackling a Beast

BY ADAM GASKA

The Right Tool for the Job

BY BRAD HALM

CHAPTER SEVEN

NINJA TACTICS

Apprentice Tent

BY JEN GRIFFITH

My First Intern Worked Pregnant for the Entire Summer

BY ERIN BULLOCK

Farming in a Climate of Change

BY GINGER SALKOWSKI

Weathering the Storms

BY KATIE KULLA

The Basket Is Half Full

BY TONYA TOLCHIN

Surviving Globalization Together

BY JANNA BERGER

Lost and . . . Still Lost

BY BEN SWIMM

CHAPTER EIGHT

OLD NEIGHBORS, NEW COMMUNITY

The Farmers’ Table BY SAMANTHA LAMB

Buried Steel BY SARAHLEE LAWRENCE

It Takes a Village to Raise a Farm BY JON PIANA

Social Farming BY JEN AND JEFF MILLER

Who Says You Can’t Go Home? BY BRANDON PUGH

Cross-Pollination BY LIZ GRAZNAK

Coming Full Circle: The Conservatism of the Agrarian Left BY VINCE BOOTH

RESOURCES

Websites of Contributing Farmers

Recommended Reading

Farm Opportunities—Apprenticeships and Jobs

Planning Worksheets

Business Planning

Land Access General Reference

Land-Linking Programs

Profits and Pricing

Taxes and Accounting

USDA Beginning Farmer Loan Literacy

Learning and Networking Conferences

Recommended Reading about Sustainable Land Management

Food Justice Organizations

INTRODUCTION

Shovel Sharpened, Shovel Ready

The essays in this collection were written and selected by beginning farmers for the benefit of other beginning farmers, eaters, and aspiring agrarians of all stripes. These stories are narratives of production that we believe to be representative of the beginning-farmer experience in contemporary American life. Directly personal, they have given us the opportunity to reflect on the shape of the movement and the implications of our collective work, which has engaged us for varying amounts of time, in every region of the country. The authors/farmers represented here dream big in very different ways.

Americans, by and large, no longer think of themselves as part of an agrarian nation. That is, most Americans are neither engaged in agriculture, nor acculturated into its rituals, nor personally connected to its success. Trade, technology, retail — these spin the economic turbines of our major cities; these dominate the headlines of our newspapers, the avenues of academia, and the imagination of our televised pantheon. Though we are fed collectively, we have, as a culture, only just begun to consider the implications of our industrialized, and continually consolidating, food system.

Viewed through the lens of public health and climate change, in particular, this examination of what and how we eat has gained national prominence. Finally, people are paying attention to the food: where it is grown, how it is processed, who owns it, what degrades and pollutes it, the impact it has on our health. This conversation is long overdue; a third of our kindergartners are predicted to contract type 2 diabetes in their lifetime, and a third of climate change is attributed to the production, manufacture, and distribution of food. We’ve reached a crisis point. The consensus is almost deafening: The food system must change.

And who will make that change? Today’s accepted rural narrative is one of crisis, abandonment, and attrition. For the past 30 years, as farms got bigger and prices spiraled ever downward, young people have been leaving agriculture and rural areas, and the rural culture has suffered tremendously for that loss. Small towns across the country stand empty and forlorn. There isn’t enough money pumping through local businesses. There are fewer and fewer parishioners and contra dancers. Mega dairies, feedlots, processing factories, and grain elevators stand tall over an agricultural landscape that is ever less enticing and less accessible to ambitious youth. Country western to country eastern, the average American farmer is 57 years old and, likelier than not, he’s on the brink of retirement or bankruptcy.

Thankfully, it is not just a cultural conversation about food that has begun in this country. There is also a quietly surging and committed movement of people who have recently, almost inexplicably, hitched their lives to agriculture. And just in time. Despite the paving of hundreds of thousands of pastures with either concrete or corn, there is still a thriving, driving need in the hearts and minds of a new generation of farmers to be makers of food, tenders of land, and protagonists of place. Bottom line: We want to and love to farm. We love to farm with such fervor that we are willing to jump high hurdles and work long hours to build a solid business around our love. It is not easy, or simple, or socially acceptable. Increasingly, though, entrants into American agriculture are propelled by a force of intention that ignores such things. Thirty years of protracted rural crisis have left quite a toxic wake: degraded soil, desperate economies, worn-down communities. With a mind for business and a brave agenda of personal, societal, and ecological sustainability, we’ve got a lot of reclaiming to do.

The work is difficult but it’s relevant. Being or becoming a farmer is a thrilling act of creation; to do so, we hold a space between the present and the future, between ecology and humanity. We are directly involved in the reconstitution of a local, resilient, and delicious food system. This impulse to farm is felt by a wide (and widening) range of Americans. We are unified in our willingness to work, to change, to sacrifice comfort and social acceptance in the pursuit of an agricultural life.

The stories here are about that work: the intentions behind it, the structural challenges, the improvised solutions, the aches and the tedium, the bliss and the sheer physical toil. We all work very hard at our businesses — growing food, educating our communities, refurbishing barns, retooling equipment — and our movement benefits from the charismatic presence of hard workers; it sets a good example.

What is it to be a new farmer in America? Some of us are punky city kids, some come from suburbia, some come from families that taught handy skills, many are the offspring of recent immigrants. This is America, and it is colorful. We’re proud of our diversity, our multicultural, multimodal, multipronged professional trajectories in agriculture. Some of us traveled east seeking roots, some traveled west seeking land. We hunted for old agronomy books in school libraries and used bookstores; we apprenticed ourselves to old ranchers and old hippies. We invent new ways of doing business in spaces designed by another era. We are Americans deeply in touch with our land, our place, and our role in re-forming that place. Our stories come from experience, but they vibrate with the anticipation of a particularly good American future.

Farming is an expression of patriotism and hope. Though our votes might be ignored in this country, as farmers we can still take pride in a nation we’ve directly cultivated. We can be proud Americans to the extent that we transform this country into a place worthy of that pride. We are still a nation of great lands and great towns. No matter where we were raised, we have come to the realization that it is our job to make it a remarkable future. And across all landscapes, suburbs, vacant lots, lease agreements, and lonely roads, we are crafting that future according to our own tastes. We stick our forks, tines, spades, and fingers into that particular part of the planet over which we have gained some governance. And, as a result, we eat well, we sleep well, and we earn the respect of our neighbors and families. Imagine: We can reshape the American landscape.

We do imagine, collectively, what our work adds up to: how it expands and extrapolates in the bellies and brains of those we feed and host and inspire on our farms. Our hopefulness has grandeur in it, not just sacrifice. We are creating our own new rural institutions of celebration and cultural interest: crop mobs and hoe downs and seed swaps. We reconfigure urban and post

industrial spaces with gardens in pots, start chicks in truck beds and swimming pools, erect temporary fencing, jerryrig air-conditioning units to keep our flowers cool. We recognize the power in DIY, the dignity of a small business, and the bold political gesture of it all. We can imagine already the outcome and consequences of our work together, the building and rebuilding of a sustainable agriculture, economy, and society. Ultimately, it’s in our hands to make it so.

We continue to exert ourselves agriculturally. Difficult choices and professional acrobatics characterize that journey. It is hard. At each step, we must often radically reshape the economy in which we farm, and radically challenge the agronomic status quo. Perhaps you will agree that the insights of beginning farmers carry crossover value for other actors in our changing society, who must face down similarly daunting personal transitions.

Thomas Edison famously said, “Opportunity is missed by many because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work.” Yes indeed, it is work. But it is work that must be done, and an opportunity not to be missed.

– Severine von Tscharner Fleming

CHAPTER ONE

BODY-HEART-SOUL

Farming. It’s physically demanding, requires entrepreneurial gumption, and tests our emotions.

When I first considered apprenticing on a farm, I was attracted to the agrarian lifestyle for its therapeutic and strengthening characteristics. Fresh, organic food would always be nearby, and I would be physically active — something that was lacking at my previous job. Still, I had some insecurity about diving into something so unfamiliar and uncomfortable. During my first farm internship, I was awkward with a hoe and tired quickly. Since then, I get stronger each season and have learned diligence, courage, and resilience.

Those lessons were reinforced this last winter during our third cool-season-vegetable CSA. Last fall and winter in northern California, rain hammered the soil for months with no mercy. Without a lot of greenhouses to protect our crops, we struggled to fill CSA shares. When it hailed in March, my heart sank. No matter what we did with the resources available, the weather kept beating us down. As tiny ice cubes pelted me and the crops, I took a long, deep breath and cried a little.

Greenhorns

Greenhorns